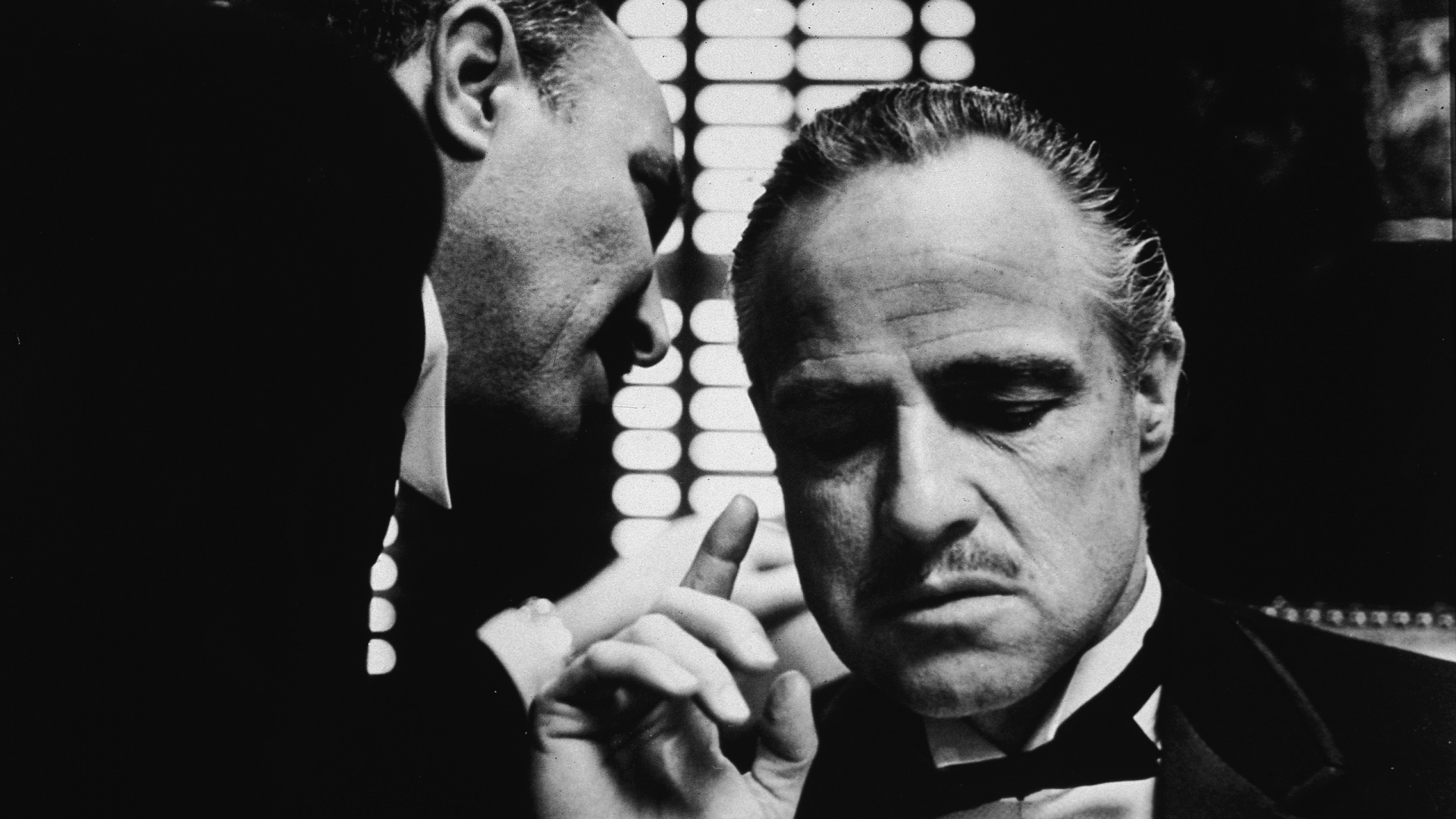

The Philippines is run like a Mafia Network

After the recent revelations of the pork barrel scam, the patronage politics exposed during the Typhoon Yolanda Tragedy and the privileged speech revelations in Senate , it strikes me that the Government of the Philippines is very similar to the Sicilian Mafia, and I’ll explain why. You be the judges:

The Mafia (also known as Cosa Nostra, in English “Our Concern”) is a criminal syndicate in Sicily, Italy. It is a loose association of criminal groups that share a common organizational structure and code of conduct, and whose common enterprise is protection racketeering, smuggling, gambling and other illegal activities. Each group, known as a “family”, “clan”, or “cosca”, claims sovereignty over a territory, usually a town or village or a neighbourhood (borgata) of a larger city, in which it operates its rackets. Its members call themselves “men of honour”, although the public often refers to them as “mafiosi”. If you examine Philippines Patronage Politics, from the Barangays all the way to the Presidency, you will note these clan and family associations.

According to the classic definition, the Mafia is a criminal organization originating in Sicily. However, the term “mafia” has become a generic term for any organized criminal network with similar structure, methods, and interests.

The Sicilian adjective mafiusu (in Italian: mafioso) may derive from the slang Arabic mahyas (مهياص), meaning “aggressive boasting, bragging”, or marfud (مرفوض) meaning “rejected”. In reference to a man, mafiusu in 19th century Sicily was ambiguous, signifying a bully, arrogant but also fearless, enterprising, and proud, according to scholar Diego Gambetta. In reference to a woman, however, the feminine-form adjective “mafiusa” means beautiful and attractive. Have a look at the Congressmen and Women, and the Senators, both Male and Female, in Philippine Politics and see how many of them fit this description.

Italian scholars such as Diego Gambetta and Leopoldo Franchetti have characterized the Sicilian Mafia as a “cartel of private protection firms”, whose primary business is protection racketeering: they use their reputation and connections to deter people from swindling, robbing, or competing with those who pay them for protection. For many businessmen in Sicily, they provide an essential service when they cannot rely on the police and judiciary, who are either corrupt or powerless to enforce their contracts and protect their properties from thieves (this is often because they are engaged in black market deals). Scholars have observed that many other societies around the world have criminal organizations of their own that provide essentially the same protection service through similar methods. Is this not similar to what occurs in the Philippines? People must resort to bribes, political connections and corrupt officials to get things done?

For instance, in Russia after the collapse of Communism, the state security system had all but collapsed, forcing businessmen to hire criminal gangs to enforce their contracts and protect their properties from thieves. These gangs are popularly called “the Russian Mafia” by foreigners, but they prefer to go by the term “krysha”.

“With the (Russian) state in collapse and the security forces overwhelmed and unable to police contract law, cooperating with the criminal culture was the only option…. most businessmen had to find themselves a reliable krysha under the leadership of an effective vor.”

—excerpt from McMafia by Misha Glenny.

Is this situation also similar to what happens in Mindanao with clans like the Ampatuans?

The Historical Context: Modern scholars believe that its seeds were planted in the upheaval of Sicily’s transition out of feudalism in 1812 and its later annexation by mainland Italy in 1860. Under feudalism, the nobility owned most of the land and enforced law and order through their private armies. After 1812, the feudal barons steadily sold off or rented their lands to private citizens, very similar to what the Wealthy Land Owning Families of the Philippines have done in the past. Primogeniture was abolished, land could no longer be seized to settle debts, and one fifth of the land was to become private property of the peasants (similar to the Hacienda Situation existing in the Philippine Context).

After Italy annexed Sicily in 1860, it redistributed a large share of public and church land to private citizens. The nobles also released their private armies to let the state take over the task of law enforcement. However, the authorities were incapable of properly enforcing property rights and contracts, largely due to their inexperience with free market capitalism. Lack of manpower was also a problem: there were often less than 350 active policemen for the entire island. Some towns did not have any permanent police force, only visited every few months by some troops to collect malcontents, leaving criminals to operate with impunity from the law in the interim. With more property owners and commercial activity came more disputes that needed settling, contracts that needed enforcing, transactions that needed oversight, and properties that needed protecting. Because the authorities were undermanned and unreliable, property owners turned to extralegal arbitrators and protectors. These extralegal protectors would eventually organize themselves into the first Mafia clans and sometimes these clans controlled, and in many cases became the local governments. Does this not sound familiar to what occurs in remote Towns and Villages in the Philippines?

In 1864, Niccolò Turrisi Colonna, leader of the Palermo National Guard, wrote of a “sect of thieves” that operated across Sicily. The sect made “affiliates every day of the brightest young people coming from the ruling class, of the guardians of the fields in the Palermitan countryside, and of the large number of smugglers; a sect which gives and receives protection to and from certain men who make a living on traffic and internal commerce. It is a sect with little or no fear of public bodies, because its members believe that they can easily elude them.” Does this not also sound like the Oligarchy and Political Elite that currently rules the Philippines? In fact, this Protection was enshrined in the Philippine Constitution of 1987, which guarantees the control of all forms of business in the hands of the Oligarchy, with no risk of Competition. In fact, the Oligarchy in the Philippines, is in fact, the Government itself.

Mafiosi meddled in politics early on, bullying voters into voting for candidates they favored. At this period in history, only a small fraction of the Sicilian population could vote, so a single mafia boss could control a sizeable chunk of the electorate and thus wield considerable political leverage. Mafiosi used their allies in government to avoid prosecution as well as persecute less well-connected rivals. The highly fragmented and shaky Italian political system allowed cliques of Mafia-friendly politicians to exert a lot of influence. The Current Dynastically Controlled Philippine Presidential System basically mirrors this set up, from the LGUs all the way to the Houses of Congress and Senate. Power rests in loose associations that masquerade as Political parties where allegiances change easily, based on power and influence. In a series of reports between 1898 and 1900, Ermanno Sangiorgi, the police chief of Palermo, identified 670 mafiosi belonging to eight Mafia clans that went through alternating phases of cooperation and conflict. How many rival clans control Philippine Politics? Read this article to find out…

Lets look at how the Elites have ruled, and continue to rule the Philippines: President Aquino is the son of Senator Benigno Aquino, Jr (“Ninoy”) who was assassinated upon return from exile in 1983, an event that touched off several years of unrest that culminated in the historic People Power revolution and the 1986 ousting of President Ferdinand Marcos. Ninoy’s father (Noynoy’s grandfather) was Benigno “Igno” Aquino, also a Senator before World War II before becoming Vice-President of the Japanese-sponsored “second Philippine Republic” toward the end of the war. Igno’s father (Ninoy’s grandfather, Noynoy’s great-grandfather) was Servillano “Mianong” Aquino, who was a general in the anti-colonial revolution fighting successively at the turn of the 20th century against Spain and the United States and who served in the revolutionary government’s Congress. Mianong’s father (Igno’s grandfather, Ninoy’s great-grandfather, and Noynoy’s great-great-grandfather) was Don Braulio Aquino who belonged to the landed aristocracy and lived 150 years before his great-great-grandson announced a run for the presidency. Noynoy is the second cousin of another failed candidate for the presidency, Defense Secretary Gilberto Teodoro. Noynoy’s mother, Cory Aquino, is a cousin of Teodoro’s mother, Mercedes. The two wings of the Cojuangco clan have been feuding for decades.

After WWII, in a strange parallel to the situation in the Philippines, the changing economic landscape of Sicily would shift the Mafia’s power base from rural to the urban areas. The Minister of Agriculture, a communist, pushed for reforms in which peasants were to get larger shares of produce, be allowed to form cooperatives and take over badly used land, and remove the system by which leaseholders (known as “gabelloti“) could rent land from landowners for their own short-term use. Owners of especially large estates were to be forced to sell off some of their land. The Mafia, which had connections to many landowners, murdered many socialist reformers. The most notorious attack was the Portella della Ginestra massacre, when 11 persons were killed and 33 wounded during May Day celebrations on May 1, 1947. Note the similarity to the Philippines and the Hacienda Luisita Massacre, among others?

Also, after WWII there was a huge demand for new homes. Much of this construction was subsidized by public money. In 1956, two Mafia-connected officials, Vito Ciancimino and Salvatore Lima, took control of Palermo’s Office of Public Works. Between 1959 and 1963, about 80 percent of building permits were given to just five people. Construction companies unconnected with the Mafia were forced to pay bribes and protection money to get permits. Many buildings were illegally constructed before the city’s planning was finalized. Mafiosi scared off anyone who dared to question the illegal building, or had them tied up in red tape or frivolous legal cases, often dragging on for years. The result of this unregulated building was the demolition of many beautiful historic buildings and the erection of apartment blocks, many of which were not up to standard. How many Philippines Construction Companies get the bulk of Philippines Government Infrastructure Jobs? Who owns these Companies? Who owns the large property development firms, how are they connected to Politics? In fact, who runs the Banks, the Power Generation Plants, the Telecommunication Networks, the Large Retail Outlets, the Cement Factories, the Media, etc?

In many cases, Philippines Public Institutions are extensions of these Mafia-like activities. Let’s take a hypothetical look at the PNP or NBI. For example: suppose a meat wholesaler wishes to sell some meat to a supermarket without paying taxes. Neither the seller nor buyer can turn to the courts for help should something go wrong, such as the seller supplying rotten meat or the buyer not paying up. The law does not enforce black market agreements; it punishes them. Without the arbitration of the law, the seller could cheat the buyer with impunity or vice versa. If the parties both do not trust each other, they cannot do business and they could both lose out on a profitable deal. Instead, the parties can approach someone they know to corrupt in the PNP or NBI, to supervise their illegal deal. In exchange for a commission, they promise to both the buyer and seller that if either of them tries to cheat the other, the cheater can expect to be assaulted or have his property vandalized. Only a fool would dare cheat somebody protected by the Mafia/Police/NBI. With the traders satisfied that this mafioso can discourage cheating, the transaction proceeds smoothly and all parties leave satisfied. The Mafia’s protection is not restricted to illegal activities. Shopkeepers often pay the Mafia to protect them from thieves, as many do the Police and NBI (based on Published News reports). If a shopkeeper enters into a protection contract with a mafioso, the mafioso will make it publicly known that if any thief were foolish enough to rob his client’s shop, he would track down the thief, beat him up, and, if possible, recover the stolen merchandise (mafiosi make it their business to know all the fences in their territory), as do the Police/NBI.

Mafiosi sometimes protect businessmen from competitors by threatening their competitors with violence or other problems. If two businessmen are competing for a government contract, the protected can ask his mafioso friends to bully his rival out of the bidding process. In another example, a mafioso acting on behalf of a coffee supplier might pressure local bars into serving only his client’s coffee. In the Philippines, Corrupt Officials fulfill this role, holding up approvals or permits until the shopkeeper complies.

The primary method by which the Mafia stifles competition, however, is the overseeing and enforcement of collusive agreements between businessmen. Mafia-enforced collusion typically appear in markets where collusion is both desirable (inelastic demand, lack of product differentiation, etc.) and difficult to set up (numerous competitors, low barriers to entry). In the Philippines, this has been set up in the Constitution, and in collusion with the Lawmakers, who themselves are the ruling business classes, including the Oligarchy. The 60/40 Rule and the FDI negative list enshrines these protection into the Constitution itself. The truth is that the power of Filipino family-based oligarchies both derives from and contributes to a weak, corrupt state. From provincial warlords to modern managers, prominent Philippine leaders have fused family, politics, and business to subvert public institutions and amass private wealth, an historic pattern that continues to the present day.

Mafiosi approach potential clients in an aggressive but friendly manner, like a door-to-door salesman. They may even offer a few free favors as enticement. If a client rejects their overtures, mafiosi sometimes coerce them by vandalizing their property or other forms of harassment. In the Philippines, often these overtures are done by local Government Officials, Police or LGUs, to extort money, products, services and favors. In fact, most Philippines Government “Service” Providers are simply Official Extortion Rackets, requiring people to pay for irrelevant “Clearance Certificates” as a form of harassment and extortion of fees.

In many situations, mafia bosses prefer to establish an indefinite long-term bond with a client, rather than make one-off contracts. The boss can then publicly declare the client to be under his permanent protection (his “friend”, in Sicilian parlance). This leaves little public confusion as to who is and isn’t protected, so thieves and other predators will be deterred from attacking a protected client and prey only on the unprotected. In the Philippines, this is the Patronage System, usually involving High Ranking Officials, or other Political Figures, local, Provincial or National.

Mafiosi generally do not involve themselves in the management of the businesses they protect or arbitrate. Lack of competence is a common reason, but mostly it is to divest themselves of any interests that may conflict with their roles as protectors and arbitrators. This makes them more trusted by their clients, who need not fear their businesses being taken over. It also leaves them free from Public Scrutiny, in the case of Philippines Officials and Politicians.

A protection racketeer cannot tolerate competition within his sphere of influence from another racketeer. If a dispute erupted between two clients protected by rival racketeers, the two racketeers would have to fight each other to win the dispute for their respective client. The outcomes of such fights can be unpredictable (not to mention bloody), and neither racketeer could guarantee a victory for his client. This would make their protection unreliable and of little value. Their clients might dismiss them and settle the dispute by other means, and their reputations would suffer. To prevent this, mafia clans negotiate territories in which they can monopolize the use of violence in settling disputes. This is not always done peacefully, and disputes over protection territories are at the root of most Mafia wars. This can best be demonstrated in the Philippines context by the Atimonan Massacre, in Quezon Province, where 13 people were killed, including high ranking Police Officials, by another Group of Police and Military personnel, allegedly working for rival Gambling Lords over a Territorial Dispute.

Politicians court mafiosi to obtain votes during elections. A mafioso’s mere endorsement of a certain candidate can be enough for his clients, relatives and associates to vote for said candidate. A particularly influential mafioso can bring in thousands of votes for a candidate; such is the respect a mafioso can command. In the Philippine Context, these endorsements can come from Celebrities and Artistes, who themselves hope to become Politicians, once their Star fades. Vote buying is also prominent and often financed by illegal activities. Politicians usually repay this support with favors, such as sabotaging police investigations or giving contracts and permits. Sound familiar?

Mafiosi provide protection and invest capital in smuggling gangs. Smuggling operations require large investments (goods, boats, crews, etc.) but few people would trust their money to criminal gangs. It is mafiosi who raise the necessary money from investors and ensure all parties act in good faith. They also ensure that the smugglers operate in safety. In the Philippines, Politicians are often the main beneficiaries and facilitators of these smuggling activities, often inserting relatives into the operation to ensure it goes smoothly. JPE the Former Senate Chairman has been known to be heavily involved in the Operations of the Cagayan Economic Zone Authority (CEZA), a renown entry point for smuggled automobiles into the Philippines.

The Sicilian Mafia in Italy is believed to have a turnover of €6.5 billion through control of public and private contracts. They rarely manage the businesses they control themselves, but take a cut of their profits, usually through payoffs. One only needs to look at the Whistle-blowers allegations in the Napoles Case to see how this functions in the Philippines. In the Philippines case, the term “Mafia”, is easily interchangeable with the “Politicians”, allegedly involved in this case, along with the Government Officials that colluded in it.

In Summation: In Italy, the term associazione di tipo mafioso (“Mafia-type organisation”) is used to clearly distinguish the uniquely Sicilian Mafia from other criminal organizations. Article 416-bis of the Italian Penal Code, under which all criminal organisations are prosecuted, defines an association as being of Mafia-type nature “when those belonging to the association, exploit the potential for intimidation which their membership gives them, and the compliance and omertà which membership entails and which lead to the committing of crimes, the direct or indirect assumption of management or control of financial activities, concessions, permissions, enterprises and public services for the purpose of deriving profit or wrongful advantages for themselves or others.”. OK, can anyone think of a more apt description of the Philippine Political Structure as outlined and exposed in the Napoles Fiasco?

YOU BE THE JUDGE.

CoRRECT™ the Constitution!

About the Author

Trevor L. Evans is the CEO of Black Hawk Inc, a Training and Simulation Solutions provider servicing the Aviation Industry throughout SE Asia. He has provided Consultancy Services for Business and Government in the Gulf Region and is formerly the Marketing & Communications Vice President for several Multi Million dollar Property Developers based in Dubai, as well as serving as the Director of Operations for the Dubai World Trade Center, the largest Exhibitions & Events Complex in the Middle East. Trevor also served as a State Police Officer and Specialist Services Officer in the Australian Army and has worked extensively in Australasia, North America, the Middle East and Europe.

Trevor currently lives in the Philippines with his Filipina wife and their Filipino children. (That’s why he cares about the Philippines: His wife and kids are Filipinos!)