KITT vs KARR: Systems & Algorithms Matter

Back in the 1980’s there was an extremely popular TV show called Knight Rider. It featured a crime-fighter with a talking car named KITT, short for “Knight Industries Two-Thousand.” KITT was a high-tech Pontiac Trans Am with a highly sophisticated Artificial Intelligence system that allowed it to assist its driver, the crime-fighter Michael Knight on his missions.

In 2 episodes, it is revealed that KITT was not the first of his kind. Instead, there was a prototype that came before him: KARR – short for “Knight Automated Roving Robot.”

Both KITT and KARR looked almost exactly alike, except that while KITT’s front scanbar had red LED’s, KARR’s front scanbar’s LED’s were amber. (In the second episode where KARR appeared, he had a paint-job to make his underside silver-gray) Despite the similar looks, they were programmed differently to have different primary objectives.

KITT, being the improvement over KARR, was programmed with an algorithm that prioritized saving the lives of KITT’s human passengers and other innocent human beings over and above its own self-preservation.

KARR, on the other hand, had been programmed with an algorithm that prioritized self-preservation above everything else.

The resulting difference was huge, despite the two Artificial Intelligence-driven cars being similar. KITT was benevolent and good. Because of its algorithm which prioritized the protection and preservation of innocent human lives, it would do whatever it could to protect its driver Michael and other innocent human beings inside it or in the vicinity. KARR, on the other hand, was malevolent. Because it was programmed to prioritize only self-preservation, it cared nothing about human beings and would use them for its own selfish goals.

The first Knight Rider episode where KARR appeared and contrasted against KITT showed the importance of having the right algorithms and the right systems to be put in place.

Which brings me to my main point: Parliamentary Systems versus Presidential Systems and the fact that their algorithms are different.

To the untrained eye, Presidential Systems and Parliamentary Systems seem similar enough that some people make the mistake of assuming that choosing one system or another does not make any difference at all. This erroneous assumption is something that many people who come from an IT or computer science background or any background involving computer programming or algorithms are often able to avoid. Because we deal with algorithms and we compare them, we do understand that some algorithms are clearly better than others, and some systems which use better algorithms are better than systems which use not-so-good algorithms.

And this is now where we look at how the Algorithms in each system are different.

Leader-search in the Presidential versus the Parliamentary System

In all presidential systems outside of the one used in the USA, Presidents are chosen by a direct national vote. That means that all votes from all around the country are counted together as one mass and whoever gets the most number of votes wins. The problem is that the people who are voting for the President aren’t always likely to have had direct experience or insight about the candidates’ working habits or their competence, and so what ends up getting played up are the candidates’ personality traits, their looks, their personal popularity, and their name-recall. Ultimately, this all gets reduced to a national popularity contest wherein the most popular and most liked candidate – not necessarily the most competent – is likely to become the president.

(In the USA, Presidents are chosen by the electorate voting for members of the Electoral College. Each state has a different number of Electoral College slots depending on their number of Congressional and Senate seats. States with very small populations have just 3 electoral college slots, while more populated ones have much more. Depending on which tandem wins in each state, the Electoral College slots will be filled by electors – members of parties fielding presidential and vice-presidential candidates – who pledged to vote for their respective parties’ tandems. If in a state with 3 electoral college slots, the Republican tandem won in the popular vote, then all of the electoral college slots are given to the electors pledged to vote for the Republican tandem. This adds an added layer, but it is this parliamentary-like layer – the electoral college – which has forcibly stabilized the US party system, forcing it to consolidate into only two parties, making it difficult for third parties to emerge.)

In short, in a Presidential System — A candidate’s popularity and/or name-recall determines whether he/she reaches the top. Full stop. The election is “one-dimensional.”

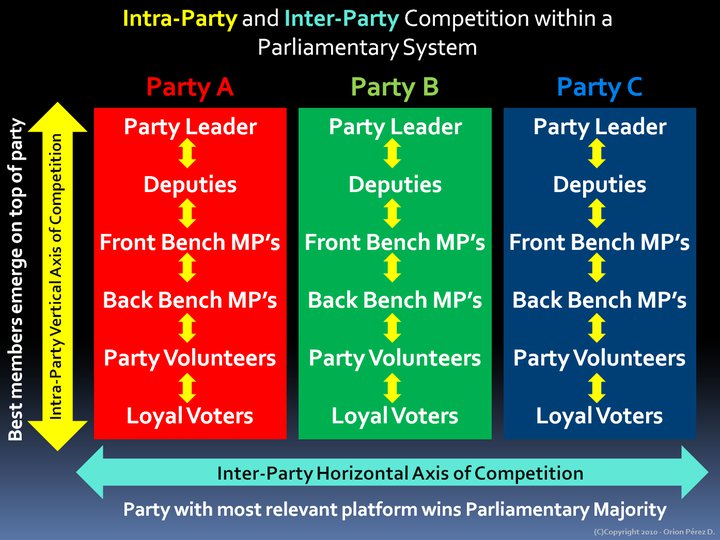

In the parliamentary system, on the other hand, the Prime Ministers aren’t chosen by a direct national vote. Instead, you have parties, and within the parties, the most competent people in the parties rise to the top and become the parties’ leaders. The contest then becomes that of having parties (not people) competing against other parties in order to get a majority of seats. The party leaders are chosen within their respective parties by party members who more-or-less would have had a much more direct experience and insight of the working habits and/or competence of their leaders. Parties, on the other hand, attract voters by talking about their platforms, policies, and proposed programmes and they explain to the voters why their respective platforms, policies, and proposals are better than those of their competitors.

Party members compete within their own parties to show who are the members who are most skillful at defending their party’s platforms and policies against attacks by other party members during parliamentary debates. As such, skilled debaters who defend the party gain brownie points in the eyes of their own colleagues and thus reach the top of their party.

In short, in a Parliamentary System — A candidate’s competence determines whether he becomes the leader of his own party, and his party’s platform and track record determines whether his party wins a majority of seats in parliament. The entire exercise is two dimensional. There is an X axis where parties compete against each other and there is a Y axis where party members compete against each other within their respective parties.

As you can see, the algorithms are different.

Presidential Systems have a one-dimensional sorting mechanism based purely on candidate popularity or name-recall. Unfortunately, candidate popularity or name-recall doesn’t necessarily correlate with ability and competence.

Parliamentary Systems have a two-dimensional sorting mechanism based on intra-party competition (intramurals) to determine which party member becomes the party leader of each party while elections provide the opportunity for inter-party competition (varsity) which party gets the most seats in parliament. Regardless of which party wins, chances are high that at the very least, the leader of the winning party is not incompetent. Besides, in a Parliamentary System, should it so happen that the majority party loses confidence in its own leader’s ability to govern effectively or competently, that leader can be very easily removed and replaced, thus changing who the Prime Minister is without stress, bloodshed, or rebellion.

Checks-and-Balances in the Presidential versus the Parliamentary System

The Presidential System works based on the principle of separating the executive and the legislative branches of government. Because of this, the Executive branch can block the Legislature’s desire to pass a particular piece of legislation or the Legislature can also block the executive’s ability to get certain things done. This separation of powers is how the Presidential System attempts to achieve “checks-and-balances” by pitting the legislative and the executive branches against each other, oftentimes leading to gridlock and shutdown. Much of the “checks-and-balances” involves after-the-fact prevention, so that after the legislature has thoroughly debated hundreds of issues relating to a bill that is to be passed into law which may have taken months or even years to debate, the President is fully capable of refusing to sign this bill into law, thus blocking its passing and wasting hundreds of man-hours spent researching, discussing, and debating the merits of a particular bill.

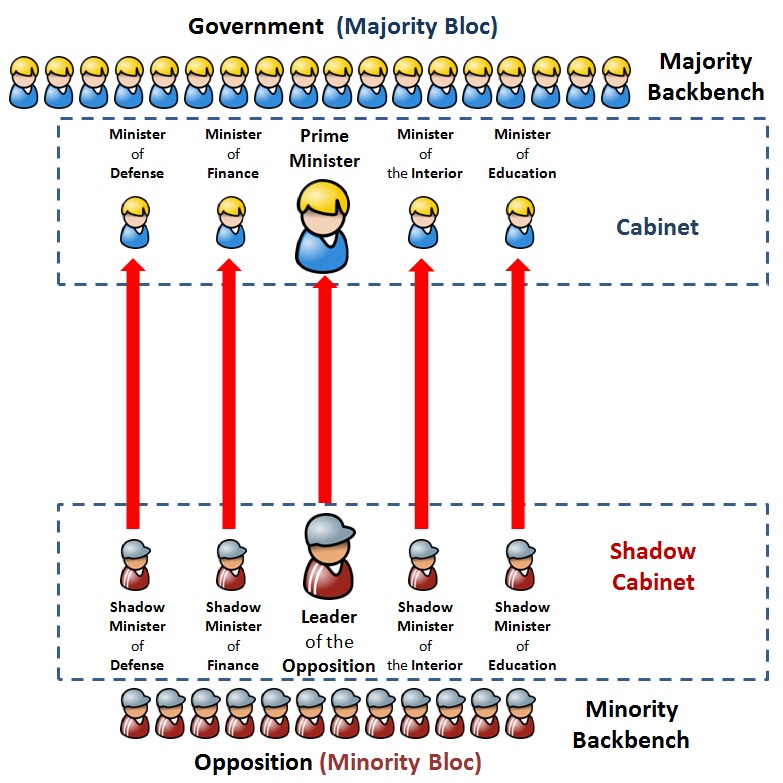

The Parliamentary System, on the other hand, works based on the principle of giving the reins of Government to the Majority Party (or coalition), while giving the ability to conduct real-time scrutiny and oversight to the Opposition Party (or coalition). The Majority party (or coalition) gets its leader taking on the position of Prime Minister, and senior members of the party or coalition get chosen to take on roles within the Cabinet to head the various Ministries based on their abilities and interests. However, the leading minority party which then takes on the role of the Official Loyal Opposition is also given official roles to play. The leader of the leading minority party becomes the Leader of the Opposition, and various senior members of the opposition party are given roles within the Shadow Cabinet to become Shadow Ministers who will follow around (or “shadow”) and constantly scrutinize their counterpart ministers from the Government, particularly during the weekly Question Time (or Question Period) which allows the Opposition to grill the Government on areas where it sees issues or problems.

Unlike in a Presidential System where “checks-and-balances” are usually done “after-the-fact”, in a Parliamentary System, the dynamics of checks-and-balances involving the Opposition’s Shadow Ministers scrutinizing the Government’s official ministers are done “in real-time.”

The Longevity Algorithm in the Presidential versus the Parliamentary System

The Presidential System uses fixed terms. In the USA, presidents are allowed two consecutive 4 year terms. In the Philippines, we only have a single 6 year term. The problem with this algorithm is that if a lousy president is elected, 6 years is a long time – as what happened with Noynoy Aquino. A good leader like Fidel V. Ramos, unfortunately, is stuck to just one 6 year term even if his policies were so good that most people wanted him to continue in order to continue pushing through with reforms that would improve the economy.

Parliamentary Systems do not have fixed terms. In most countries with parliamentary systems, there is a 5 year time-limit for which a government may be in power. Within the 5 year limit, a government may decide to call for snap elections within the 3rd or 4 year if the Prime Minister and his team feel that their performance is positive and their likelihood of winning is high, and perhaps even gain more seats in the process. It is thus in the best interest of a party that is in power to keep on performing positively for their team to remain in office. If a party in power waits too long before calling an election, it will have no choice but to call for one when the 5 year limit is over. The risk, thus, is that if a party waits too long, its own popularity might not be that great by the time the elections happen. It is thus much more favorable for ruling parties to proactively decide to call for elections right after a decisive victory or a very positive achievement. Notice that the word used is “team.” This is because in this case, a government isn’t based solely on who the Prime Minister is. It is based on the composition of the team. In fact, while Presidential Systems’ administration often bear the names of the President (like the “Obama Administration” or the “Noynoy Aquino Administration”), in Parliamentary Systems, chances are higher that governments are referred to by the party in power (“The PAP Government in Singapore” or “The Tory Government in the UK”).

Decision-Making in the Presidential versus the Parliamentary System

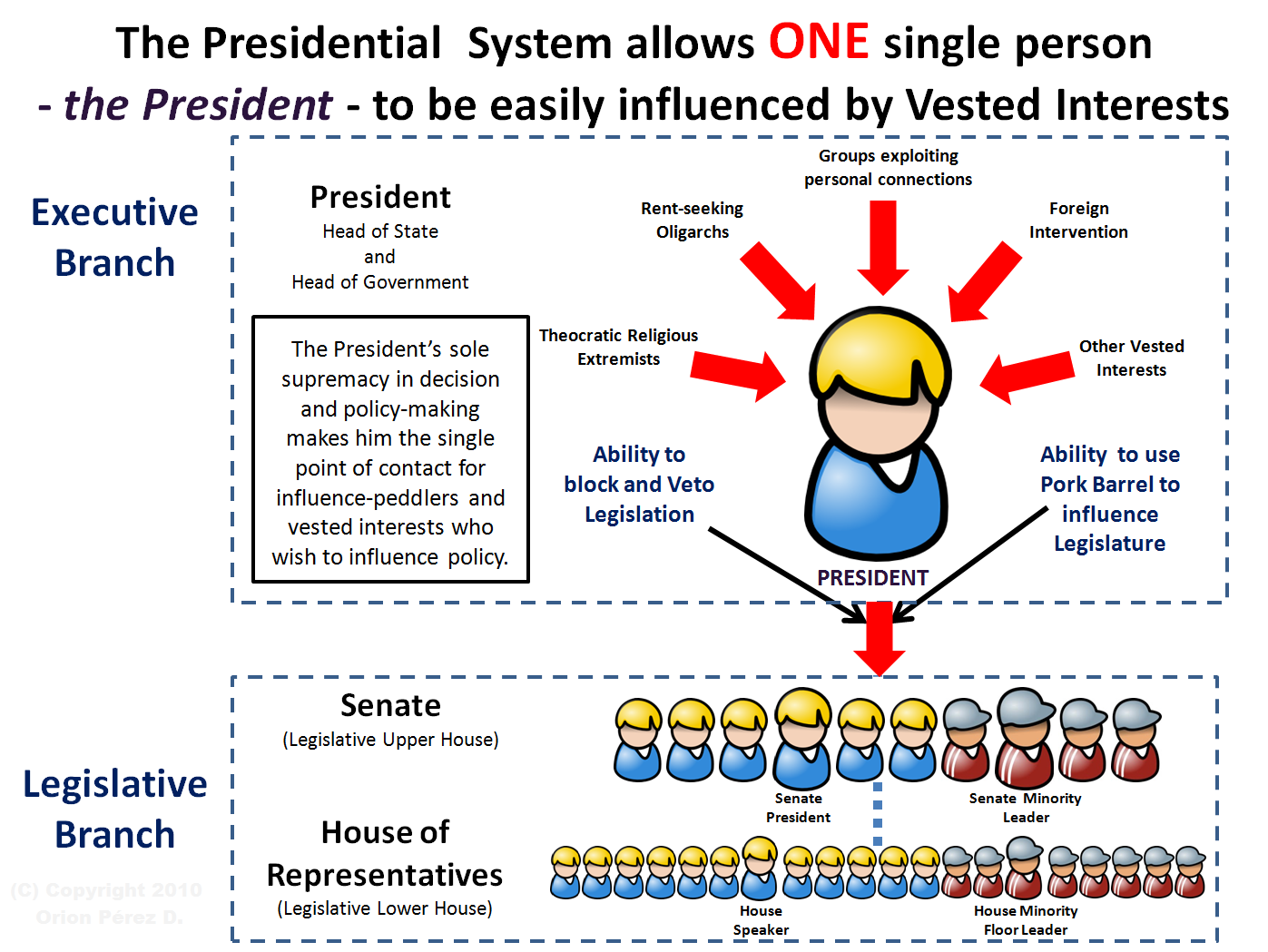

Presidential Systems generally feature unilateral decision-making – a kind of “one-man decision-making” framework, where the President alone makes decisions, and is merely assisted by his secretaries. Decision-making responsibilities aren’t really shared, due to the principle of supremacy by which the President is above everyone else and all decisions of the executive branch ultimately fall to him and not to his party. In the Philippine context, as well as in numerous other presidential systems in Latin America, there is a situation known as hyperpresidentialism in which the President also has undue influence over the legislature usually in the form of Pork Barrel funds and the ability to make use of discretionary funding to be released or withheld depending on whether a legislator has indicated support or opposition towards the president’s agenda.

In the situation of the Philippines and other Presidential Systems, this creates a single point of failure so that in case a president is unduly influenced, bribed, or coerced into making specific decisions, the entire country has no choice but to go with such decisions because everything is controlled by just one person. Outside influences may cause the president to decide in one way and the president may then cause the legislature to go the same way. It is also perfectly possible for the president to block legislation through a veto if the president gets influenced, bribed, or coerced into doing so by certain vested interests.

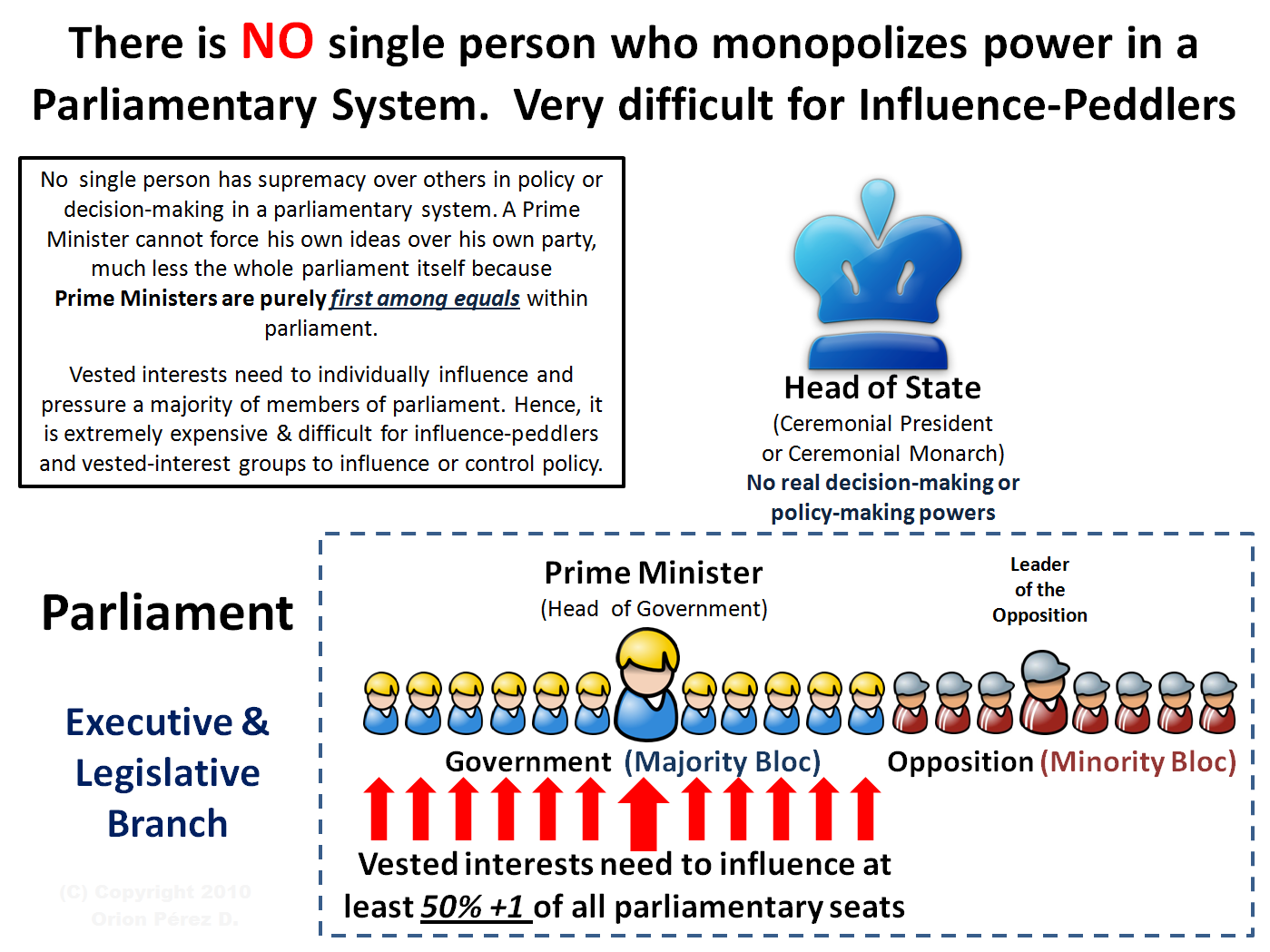

In Parliamentary Systems, however, decision-making is shared. The Prime Minister is only first-among-equals and thus has only one vote and thus cannot force others to vote the way he wants them to. His only way to do so is to convince a majority of members of parliament – his own party-mates – to support a proposal he is pushing for based on the logical and factual merits of the proposal and get that majority voting for it.

As such, there is no way for any vested interests to influence one person to get him to cause the rest to go the same way. Even if a rich businessman convinces the Prime Minister to favor his own company and give him a government contract even when other better companies exist, the other members of parliament (yes, even if they are the Prime Minister’s own fellow party-mates) will obviously question why the Prime Minister is trying to push everyone else into agreeing with such a decision. Noting that the Opposition plays an active role as the Opposition Shadow Cabinet, the Leader of the Opposition will grill the Prime Minister to demand an explanation for such a questionable move.

In fact, if the unscrupulous rich businessman wants to bribe his way to get his business favored, he will need to bribe 50%+1 (at the very least) of all members of parliament to get them supporting his cause. And no member of parliament will want a small paltry sum if it means doing something so obviously wrong for which a scandal could destroy his own reputation. While a rich unscrupulous businessman could easily just bribe one person – the president – into granting him exclusive contracts, that same businessman would find it extremely expensive to bribe 50%+1 of all members of parliament, since he obviously cannot bribe the Prime Minister who only has one vote.

For this very reason, Parliamentary Systems are much less prone to meddling and corruption than Presidential Systems.

Political Parties in Presidential Systems versus Parliamentary Systems

Many not-so-informed Filipinos (particularly members of the so-called “intellectual elite”) have a tendency to use the argument that “The Parliamentary System requires a good party system with disciplined parties for it to function properly. Look at the parties we have, they aren’t even real parties, so how can we expect to have a functioning parliamentary system if these are the kinds of parties we have right now?”

It’s just wrong thinking on their part, actually. Because they never cared to analyze the fact that the lousy parties that we have in the Philippines right now are the result of the lousy Philippine Presidential System we have. In fact, in a book entitled “Presidential Bandwagon: Parties & Party Systems in the Philippines”, Japanese political scientist Dr. Yuko Kasuya explained that there are several flaws (or “features”) of the current 1987 Constitution’s Philippine Presidential System which have totally weakened the party system. The fact that the Office of the President has the power of the purse over special funds for disbursement is one of these “features” which weakens the Philippine party system aside from the banning of a duly-elected president from running for re-election.

Back in the old days when Presidents were allowed to run for re-election, political parties were much stronger and were mostly just limited to two: the Nacionalista and the Liberal. The fact that an incumbent president who was elected as president (not someone elected as VP and took over from a president who died) could run for re-election actually meant that the other parties needed to consolidate rather than split the vote by having too many players. When the 1987 Constitution banned duly elected presidents from running for re-election, the presidential elections became a random free-for-all which caused the proliferation of candidates as well as parties.

It is precisely the features of the 1987 Constitution-defined Philippine Presidential System that has caused the party system to be weak. On the other hand, a shift to the Parliamentary System will force parties to immediately strengthen, particularly because of the need for constant debate around policies and decisions and the fact that parties inside parliament will not just concern themselves solely with legislative concerns but instead will need to take care of both executive and legislative concerns.

When some people say that “The Parliamentary System requires a good party system with disciplined parties for it to function properly. Look at the parties we have, they aren’t even real parties, so how can we expect to have a functioning parliamentary system if these are the kinds of parties we have right now?” they totally miss the point because they do not realize that the only way to fix the party system is precisely to shift over to a better system which rewards strong parties and punishes weak parties. The current Philippine Presidential System is precisely why our party system sucks. By shifting over to a Parliamentary System, our parties will be forced to become disciplined as weak parties will not succeed in getting things done, while strong and disciplined parties will clearly succeed. Why stick with the current Philippine Presidential system which doesn’t really need parties anyway since our lousy system allows a presidential candidate from party A and a vice-presidential candidate from party B to win?

About the Author

Orion Pérez Dumdum comes from an IT background and analyzes systems the way they should be: logically and objectively.

Being an Overseas Filipino Worker himself, he has seen firsthand how the dearth of investment – both local and foreign – is the cause of the high unemployment and underemployment that exists in the Philippines as well as the low salaries earned by people who do have jobs.Being Cebuano (half-Cebuano, half-Tagalog), and having lived in Cebu, he is a staunch supporter of Federalism.

Having lived in progressive countries which use parliamentary systems, Orion has seen first hand the difference in the quality of discussions and debates of both systems, finding that while discussions in the Philippines are mostly filled with polemical sophistry often focused on trivial and petty concerns, discussions and debates in the Parliamentary-based countries he’s lived in have often focused on the most practical and most important points.

Orion first achieved fame as one of the most remembered and most impressive among the winners of the popular RPN-9 Quiz Show “Battle of the Brains”, and got a piece he wrote – “The Parable of the Mountain Bike” – featured in Bob Ong’s first bestselling compilation of essays “Bakit Baligtad Magbasa ng Libro ang mga Pilipino?” He is also a semi-professional Stand-up Comedian who won first place in the 2014 Magners Singapore International Comedy Festival Best New Act Competition and is the January 2016 Comedy Central Comedian of the Month. He is the principal co-founder of the CoRRECT™ Movement to spearhead the campaign to inform the Filipino Public about the urgent need for Constitutional Reform & Rectification for Economic Competitiveness & Transformation.