A Tale of Two Countries

(Borrowed from the Far Eastern Economic Review)

by William McGurn (June 1994)

Editor’s note: While it is true that this is an old article from June 1994, the author William McGurn’s analysis is so spot-on and remains extremely relevant today such that this article seems as if it was written just yesterday. If anything, it is worth noting that the Philippine situation is even far worse now (some 20 years after this article was written) so that whatever the author wrote in 1994 has become even worse in terms of degree. That this article was written in 1994 does not diminish the Truth that this article speaks.

The human costs of protectionism

Teresa Concepcion had high hopes for her future.

Although her father was only a farmer with a grade-school education, things were looking bright for the new generation of Filipinos. By the time Teresa (not her real name) was born, the country had risen from the ashes of World War II to achieve not only independence and a working democracy but the second-highest standard of living in the Far East after Japan’s. In 1970 she entered a local university. Four years later, degree in hand, she took a job as a social worker supervising day-care centers. That’s when her dreams began to dissolve.

Teresa had expected only a modest salary. Upon entering the working world, however, she was stunned to find out exactly how low wages were, not only in her profession but throughout the Philippines. Her paycheck brought in barely $40 a month. By now she was married and had given birth to the first of three sons. Her husband, a surveyor’s assistant with the Bureau of Land and Natural Resources, made no more than she did. Even such basics as clothing and baby food became more than they could afford. And so, after eight years of incessant financial struggling, Teresa and her husband made a critical decision.

In the summer of 1983, she hugged her husband and three boys–ages 7, 5, and 3–and, with money borrowed from her in-laws, boarded a plane bound for Hong Kong at Manila Airport. At age 33, she was leaving her family behind to begin a completely new career: as a maid.

Teresa was not alone. Some 105,000 Filipinas labor in Hong Kong as amahs, or maids. Almost a decade after the People’s Power revolution that toppled Ferdinand Marcos, the plight of these women remains a standing indictment of the Philippine government’s staunchly protectionist economic policies. Like Teresa, the amahs are for the most part smart, relatively well-educated women who found the door of opportunity slammed shut at home. They have college degrees in disciplines ranging from accounting to education, yet they find themselves cooking meals and scrubbing floors for Hong Kong shop clerks and secretaries. Like Teresa, many of them are mothers who are now raising other people’s children while their own grow up without them. Underscoring their predicament is a cruel irony: A generation ago, Filipino families imported Chinese maids.

Today the situation has reached crisis proportions. Within East Asia, disparities in prosperity have led to huge labor outflows, mostly from poorer countries such as the Philippines to richer ones such as Hong Kong, Singapore, and Korea. The maids are only the legal tip of a Filipino iceberg that includes such diverse occupations as nightclub dancers, construction workers, shop clerks, and mechanics. Their growing numbers and negative image have become sensitive issues both at home and abroad. When Teresa first arrived in Hong Kong 10 years ago, there were only 24,800 Filipina amahs at work; now there are more than four times that many, and locals complain that the women occupy the city center on Sundays, their one day off.

In the Philippines, the debased condition of these women has led to legislation calling for an end to the Overseas Worker Program. In 1993, Philippine public opinion was outraged by the death of a Filipina nightclub hostess in Japan whom Japanese authorities said died from hepatitis but whose family claimed she had been beaten. Filipinos are also upset by the virtual identification of domestic with Filipina throughout the region.

The current president, Fidel Ramos, has vowed to reverse some of the longstanding policies that have sent so many Filipinos abroad–a promise that the Philippine people have heard many times before. Ramos’s biggest obstacle is a reluctance among the Philippine establishment to admit that its self-perpetuating economic policies are largely responsible for the country’s descent into poverty.

Over the years, Philippine leaders have ascribed their abysmal economic failure to any number of root causes, including their colonial heritage, Marcos-era greed, and a series of natural disasters. The truth, however, is that the country’s poverty is no accident and the quandary in which Filipina maids find themselves owes itself almost directly to the most pernicious of economic sins: protectionism. For the past 40 years, under the guise of ensuring the country’s economic sovereignty, successive Philippine governments have enacted laws that have discouraged foreign investment, concentrated wealth in fewer and fewer hands, and diminished the standard of living for the average Filipino to the point where less than 50 percent of the country earns a subsistence wage.

Nowhere is this clearer than in a comparison between the Philippines and Hong Kong, just a two-hour flight from Manila and the destination of so many Filipino laborers desperate for work. Just as the Philippines owes its current status as “the sick man of Asia” to longstanding protectionist policies, Hong Kong owes its stupendous wealth today to an ongoing commitment to open markets and a hands-off approach to business. For the past decade, Hong Kong has boasted an unemployment rate of under 2 percent, and its residents purchase more each year than the Japanese, other Asians, or Europeans. In 1993, Hong Kong’s per-capita income even surpassed that of its colonial protector, Great Britain.

But Hong Kong was no more destined to be wealthy than the Philippines was destined to be poor. If anything, it was a prime candidate for the sort of economic anemia that afflicts the Philippines. Lord Palmerston’s remark about Hong Kong upon its 1842 acquisition by the British–he called it “a barren island with hardly a house upon it”–was a fair description of its seeming promise, and even today its crowded population is spread over an inhospitable terrain that makes it utterly dependent on its neighbors even for basic resources such as water.

If Hong Kong’s natural obstacles to wealth were considerable, the man-made ones were downright staggering. No sooner had the colony begun to recover from the Japanese occupation of World War II than the Communist takeover of the mainland sent hundreds of thousands of desperate refugees to its shores. A few years later, a United Nations-imposed boycott of China saw Hong Kong lose its largest market overnight. Back in the 1950s and ’60s, the experts were not talking about the “Hong Kong miracle.” Back then, they were wondering if Hong Kong would survive.

Hong Kong withstood these pressures primarily by remaining open to foreign investment. While the Philippines and other East Asian nations chose to coddle their industries and put their faith in central planning, Hong Kong forced all its industries to compete with the rest of the world on their own merits and on a completely equal basis. And now, when countries such as South Korea are busy trying to pare down huge bureaucracies spawned by protectionism, Hong Kong is free to do productive business. There are no foreign exchange controls, and foreign companies are free to take their profits out if they choose. Taxes are stable and minimal, with none on capital gains and a flat tax on corporate profits. As Milton Friedman once quipped, “To see how the free market really works, Hong Kong is the place to go.”

This prosperity and freedom are largely the legacy of Hong Kong’s legendary financial secretary, John James Cowperthwaite. During the 1960s, Hong Kong was said to be governed “by the gospel of Adam Smith as expounded by his disciple John James Cowperthwaite.” Arriving in the colony as acadet officer in the civil service just three months after the Japanese surrender and charged with getting the economy back on its feet, Cowperthwaite immediately noted the degree to which Hong Kong’s resilient economy had already recovered without any government help. Cowperthwaite’s strength was that, more than most, he understood that even the most brilliant planner was no match for the collective genius of the market.

Whether it was water–which in those days was always in short supply–or food or energy, Cowperthwaite insisted that the best way around the problem was to allow free pricing among suppliers and to keep the doors open to anyone who wanted to enter. He did his part by keeping taxes low and refusing to spend more than he took in. “I see no reason,” he once said to a request for government to finance lower water rates, “why someone who is content with a cold shower should subsidize someone who is able to luxuriate in a deep hot bath.” Cowperthwaite, in fact, was so distrustful of intervention in the economy that he refused to allow the government to keep statistics on gross national product–on the grounds that if the government kept the statistics they would only misuse them.

This strategy was not simply do-nothingism. At the same time the government was keeping taxes low and spending under control, it embarked on a public housing scheme that would eventually shelter more than half the population. The difference was that Cowperthwaite could afford to do this since he maintained fiscal restraint and resisted calls to subsidize Hong Kong industry or give them any protection.

“Had Cowperthwaite taken the advice or yielded to all those who wanted more government intervention,” says Richard Wong of the Hong Kong Center for Economic Research, “Hong Kong would not have prospered. By keeping Hong Kong open he ensured that it would remain competitive.”

Certainly history has vindicated Cowperthwaite’s judgment. During the 10 years between 1961 and 1971 that Cowperthwaite was Hong Kong’s financial secretary, income grew faster there than anywhere else in Asia. The policy of keeping the door open to imports also fueled an export boom–at a phenomenal average annual rate of 13.8 percent over these years. Real wages increased by more than 50 percent over this period and remain roughly twice those of both Korea and Taiwan.

Hong Kong’s disavowal of protectionism extends to the lack of anti-dumping laws that are used even in the United States to keep competitors out. “Any economist will tell you that when you keep foreign business out you simply hurt your own people,” says Hong Kong treasury secretary and former trade negotiator, Donald Tsang. “All you are doing is cutting your nose off to spite your face. We keep our economy open because it is in our self-interest.”

(Note: Sir Donald “Bow-tie” Tsang went on to be Hong Kong Chief Executive at the time when Noynoy Aquino committed terrible embarrassing diplomatic blunders during the HK Tourist Bus Hostage Crisis.)

If Hong Kong owes its impressive wealth to a conscious political decision not to micro-manage the economy, the Philippines’ pervasive poverty represents the negative version of the same argument. There, a series of conscious economic choices made over the past four decades–especially a hostile attitude toward foreign investors–has allowed local monopolies to flourish at the expense of both workers and consumers.

Some have called it “crony capitalism.” But the preferences enjoyed under this arrangement have little in common with capitalism, and the cronies would lose their protected empires tomorrow if the state weren’t propping them up. The ruling elite in the Philippines has taken a country with a well-educated English-speaking work force and an enviable location smack dab in the midst of the world’s fastest growing market and turned it into an economic basket case.

This took some doing. Providence had bequeathed the Philippines many advantages, including an almost inexhaustible supply of natural resources: gold, iron ore, copper, cement, salt, granite, marble. Its soil was rich and its produce bountiful, including rice, sugar, coconuts, tobacco, bananas, and avocados. In the late 1950s and early ’60s, it was second in Asia only to Japan, and everyone assumed that its future would be as bountiful as its present.

As the World Bank put it in an upbeat report, “By comparison with most underdeveloped countries, the basic economic position of the Philippines is favorable…. |Apart from its~ generous endowment of material resources and high level of literacy, other favorable factors are the growth of the labor force, the availability of managerial and technical skills, the high level of savings and investment, rather good prospects for most of the Philippines exports, and considerable possibilities for import substitution.” The Philippines was considered so successful, in fact, that in the ’60s Manila was sending specialists to Korea to advise them on their development.

But the Philippines never realized its potential. Instead opening the door to foreign investors with the money and the wherewithal to make something of its resources, the Philippines wrapped itself in the cloak of protectionism. Under the guise of nationalism–the country had achieved independence in 1946–the Philippines passed a series of laws limiting what they called “alien” (foreign) involvement in the economy. It started with a limit imposed on alien-owned market stalls in Manila and soon covered everything from access to credit to quotas on imports. By the end of the ’50s, this had evolved into a full-fledged ideology called “Filipino First” that would figure prominently in the presidential elections for years to come.

In 1960, Philippine President Garcia summed up the Filipino First policy as merely “an honest-to-goodness effort of the Filipino people to be master of their own economic household.” His secretary for commerce and industry, Manuel Lim, likewise described the policy as simply an effort to ensure that Filipinos get some share of the benefits flowing to foreign investors. Of course, it was slightly more than this. Although both Garcia and Lim went out of their way to say the Filipino First policy would be fair to outsiders, they both saw foreign involvement in the economy as a “threat” and a cause for alarm. Although the policy was later relaxed somewhat, the emphasis remained on ensuring Philippine “supremacy.”

“It’s the classic mistake for developing countries,” says Richard Wong. “Despite all the populist rhetoric, whenever you make it more difficult for foreigners, all you are doing is taking money from the public and putting it into the hands of the vested interests.”

In the Philippines, protectionism was intertwined with racism. Many of the local entrepreneurs belonged to the country’s sizable Chinese minority, and many of the government regulations attempted to force them from their economic niches. Two of the most infamous regulated participation in retail selling and the corn and rice industries. In June 1954, President Ramon Magsaysay signed “An Act to Regulate the Retal Business,” which was followed by a 1964 measure that tightened the screws even more. The gist of the regulations was that no industry or store could sell directly to the public unless it was Filipino owned; otherwise the business had to sell to a Filipino first. The object was to make sure that Filipinos got a piece of the action on every sale. But in practice, the regulations simply created a middleman who raised the final cost to the consumer. The almost-immediate effects included a precipitous drop in the number of newly registered retail businesses and a sharp rise in general prices.

Much the same thing happened in 1961, when the Philippines passed another protectionist act, this one “Limiting the Right to Engage in the Rice and Corn Industry to Citizens of the Philippines.” Like the retail business law, this one took aim at the Chinese merchant population by decreeing that only Filipinos would be allowed to participate in rice and corn production. This was a big decision, because at the time rice was both the chief staple of Filipinos’ diet and a significant commercial export. In 1960 there had been 6,100 foreigners registered in the rice and corn business, but by the summer of 1962 the executive director of the Rice and Corn Board, E. V. Mendoza, reported that the program had “worked” in running foreigners out.

“Success,” however, was curiously defined. Apart from encouraging fraud–some foreigners simply put their companies in the names of their Philippine wives or friends–it had a disastrous effect on production and prices. Mendoza was correct in noting that by year’s end most of the rice and corn business was forced out of foreign hands. But the price paid by the population for that change was a severe rice shortage. The Philippines went from a country that exported rice to one that imported it, a situation that did not change until much later in the decade when scientific advances introduced a new, “miracle” rice capable of tremendous new yields.

The government’s continuing support of protectionist policies in the face of such abject failures is the reason why Max Soliven, editor of The Philippine Star and the country’s most popular columnist, blasts the Filipino First philosophy as “the pirate flag of convenience for vested interests.”

“Every big foreign investment project,” says Soliven, “is slandered as ‘a scam’ or labeled ‘imperialist exploitation,’ and thus those two cabals of conspiracy, the Old Rich and the nouveau riche, manage to fight off and repel ‘the enemy.'” Filipino First, says Soliven, should really be called “Filipino Last and Always.”

As far back as the early 1960s there were voices raised in warning. In 1962 the president of the Philippine Chamber of Commerce, Alfonso Catalang, went on television to say that Filipino First was shooting the country in the foot. My magazine, the Far Eastern Economic Review, warned that “Filipino politicians seem to favor securing foreign loans instead of inviting foreign capital to come in.” The direct result of such choices were the bloated Philippine monopolies that still stand before us today, protected from foreign competition and unresponsive to the needs of the country.

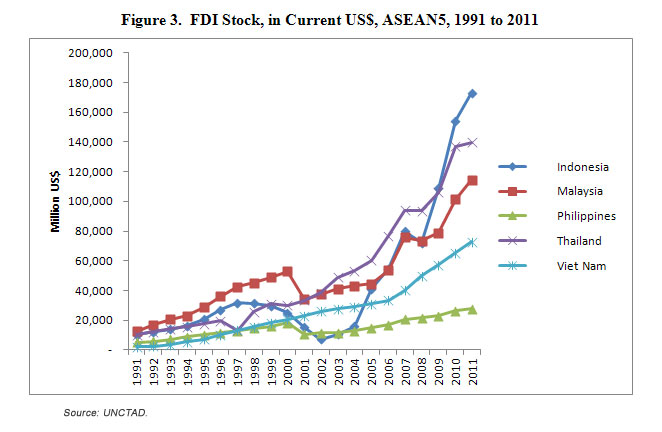

Although myriad regulations restrict foreigners doing business in the Philippines–foreign banks, for example, have not been permitted to open new branches since 1948–the most effective way of keeping them out has been a law limiting the amount any foreigner can own in a business to 40 percent. At the start of his reign, President Marcos made some moves to open up the economy, but instead of busting the monopolies he merely put his own buddies in charge of them. Nor did things improve with the People Power revolution of Cory Aquino. By 1991 foreign investment in the Philippines totaled only $783 million–compared to about $5 billion for Thailand and almost $9 billion for Indonesia, which is just about as poor as the Philippines.

In many ways, in fact, Aquino only made the situation worse. The constitution drafted by her associates specifically blocks or severely limits access to vast segments of the economy by outside developers, especially in the area of natural resources. Section 12, for example, requires that the “State shall promote the preferential use of Filipino labor, domestic materials and locally produced goods.” In effect, the revised constitution applies the 40-percent limit to all but a few areas. Filipino First is back with a vengeance.

The reason the 40-percent limit is so debilitating is that as long as votes in a company are pegged to the owner’s share, no foreign investor will have control over his money. This is particularly distressing in a developing country such as the Philippines, where the economic climate is uncertain and the risks are already high. Foreigners are unlikely to invest millions of dollars if they don’t have a say over how the money will be spent.

“If I had to name one thing that has hurt the Philippines more than anything else, it’s this 40-percent limit,” says Peter Wallace, an international business consultant and economist who has lived in Manila for many years. “We had a similar problem in Australia years ago–we were resource rich but cash poor. Much of Australia’s development came about because it opened the door to those who had the money to develop, especially in the mining industry.” In testimony before the Philippine Congress, Wallace pointed out that if the Philippines followed Australia’s lead, the country’s abundant resources would finally start paying some dividends.

The development of natural resources is hardly the only area of the Philippines’ economy affected by the lack of foreign capital. The nation’s infrastructure, for example, remains one of the worst in Asia. President Ramos has recently eased the ongoing power shortage that just last summer was responsible for blackouts of 10 to 12 hours a day. But the shortage never would have occurred had the country opened energy development to foreigners. “Making yourself open to foreign investment does much more than bring in money,” says Wallace. “It brings in badly needed technology. It grows your exports. It creates jobs, and it generally also develops a host of industries that pop up to serve the new investors.”

The Philippines’ nationalism has, in fact, managed to strangle every aspect of economic development. Foreign goods remain a luxury that only the protected rich can hope to afford. Recently Philippine Sen. Blas Ople pointed to a study by the government’s own assistant secretary for trade documenting that no less than 167 signatures were necessary to release an imported car from the Bureau of Customs. Ople had a field day when the customs commissioner proudly announced he had greatly reduced the number of necessary signatures: to 50.

The regulatory choke hold is also responsible for a phone system so abysmal that it is an international embarrassment. In a November 1992 visit to Manila, Singapore’s senior minister, Lee Kuan Yew, publicly spoke out against the Philippine telephone company as “an example of a powerful vested interest … which has had a monopoly for 64 years.” He also cited a standing joke that “98 percent of Filipinos are waiting for a phone and the other 2 percent are waiting for a dial tone.” In fact, fewer than 2 out of 100 Filipinos have phones in this nation of 61 million people, and the Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company controls more than 90 percent of the existing 600,000 lines. Their monopoly has been helped along by Supreme Court decisions that shut Eastern Telecommunications out of the market and awarded a contract to PLDT even though its foreign-backed competitor had outbid it by a factor of six.

Comparing the Philippines’ phone system to Hong Kong’s actually provides a thumbnail sketch of how two economic systems produce hugely different results. While the Philippines stagnates with one of the worst phone systems in the world, Hong Kong boasts one of the best: fully digitalized with about 63 phones per 100 population, about double the number of another East Asian powerhouse, South Korea. It is so easy to get a phone in Hong Kong that almost all the colony’s shops have a phone sitting out front that customers can use free. And with new developments in related technology (such as cellular phones) now becoming popular, the government reviewed its telecommunications policy and decided to open up additional networks to increase competition.

Beyond all the theoretical and statistical explanations, however, the painful human costs of the different economic strategies pursued by Hong Kong and the Philippines are dramatically illustrated by the booming growth of domestic helpers in Hong Kong. A generation ago, middle and upper-class Filipinos were likely to have poor Chinese as amahs. Today the situation has flip-flopped. Thousands of desperate Philippine women just like Teresa Concepcion–college educated and with children of their own–are forced by circumstances beyond their control to go abroad and work as domestics. The ones who are lucky go to Hong Kong. Many go to the Middle East or other parts of Asia, where the work is even more demanding and the environment even more difficult.

Life on the bottom rung of society has its other problems as well. Filipinas often report that the Chinese look down on them and treat them harshly. Indeed, one of the colony’s biggest companies, Hong Kong Land, recently tried to bar them from sitting on its grounds on weekends when they congregate with their friends in the center of town.

Occasionally, their work may even prove fatal. One Filipina, Pascuela Destas, gave her life for her 5-year-old charge by pushing him out of the way of an out-of-control bus. But saving the life of her employers’ son meant that Destas left her own three boys back in the Philippines without abreadwinner.

Although life in Hong Kong may be difficult, the maids agree on one thing: It is better than being in the Philippines. Thirty-eight-year-old Eppie Cruz is typical. Ten years ago she received her B.S. in accounting from the Philippines’ University of the East. After her graduation, she came to Hong Kong to work as a domestic to support her sisters back home. “Of course we would like to stay in the Philippines if the opportunity was there,” says Eppie. “But the jobs are here.”

Eppie is wearing a Giordano blouse, a popular brand in Hong Kong roughly equivalent to the Gap in America. In the Philippines, she says, it would cost three times as much as it does in Hong Kong. The same goes for her Sony Walkman. Back in her tiny room, she has a telephone, an air conditioner, a JVC television, and a host of minor appliances that are standard in Hong Kong but would be regarded as luxuries in the Philippines.

Or consider 49-year-old Cora Alanunay. Cora is the mother of six children–two of whom are with her in Hong Kong, also working as domestics. One son, Ramon, is working in a hospital in Saudi Arabia. She came to Hong Kong shortly after she was widowed and needed work, and like her friends she is impressed by Hong Kong’s commercial openness and the opportunity it breeds. Although Cora makes only a minimal wage in Hong Kong, it’s far more than what another son makes back in the Philippines as a bank executive.

The incentives are as clear as they are heartbreaking. Today Teresa Concepcion’s children are 16, 14, and 12. Since leaving the Philippines nine years ago, she has seen her boys and her husband just once each year for a few weeks’ holiday. Yet she has little choice. Her salary of $520 per month is 13 times what she could hope to make in the Philippines, and each month she mails half of it back home. Like other Filipina exiles in Hong Kong, Teresa stoically accepts the trade-offs: “I constantly remind myself how important it is to send back the money to them. Otherwise I would get depressed thinking about the kind of work I’m forced to do.”

These amahs are not alone. Ever since the Philippines started its Overseas Employment Program in the mid-1970s, hundreds of thousands of Filipinos who would otherwise have stayed at home have gone into exile to provide for their families. They have also provided for their country. Last year, the 4.5 million Filipinos working abroad helped bail out their country’s cash shortages by sending home an estimated $2.5 billion in foreign exchange-more than the revenue from a number of important Philippine industries, including tourism.

Having inherited an economy that so demeans productive workers, President Ramos has moved to open up the banking system and, most recently, has vowed to fulfill promises to sell off state enterprises. But the problems remain formidable–particularly the protectionist constitution that walls off investment in any number of areas and a Filipino First legacy that endures. Perversely enough, at a time when the Philippines ought to be out begging for multinational investment, a major argument in the national legislature against the privatization of firms such as Petron Oil is that they may be bought by foreigners.

Ramos, too, for all his stated intentions to the contrary, is not above playing the old games. Back in 1975, Imelda Marcos erected pretty white fences so that the delegates to the annual IMF/World Bank meeting would not have to be offended by the sight of the very poor they were supposed to serve. Last year on May Day, President Ramos announced plans to close the Smoky Mountain garbage dump–long a favorite of foreign reporters looking for a symbol of the Philippines’ crushing poverty. The thousands of scavengers who eke out an average $3.00 per day picking through Smoky Mountain’s waste for anything they can sell, use, or eat are upset that the government is once again taking away what little livelihood they have. The Philippine poor will be forced to move out of sight, if not out of poverty.

And in Hong Kong, Filipina mothers and daughters continue to pay a devastating social and economic price for the protectionist schemes of their government. Most of these women started out with big dreams; Teresa Concepcion thought that with her college degree she’d have a fulfilling career in the Philippines, not a job scrubbing floors in Hong Kong. Today she just wants to go home. “I’d like to return to the Philippines in two or three years,” she says, “maybe to farm with my husband.” Even if she is lucky enough to do so, it will mean her children will have grown up without her. What kind of protection is that?

William McGurn is a senior editor at the Far Eastern Economic Review.